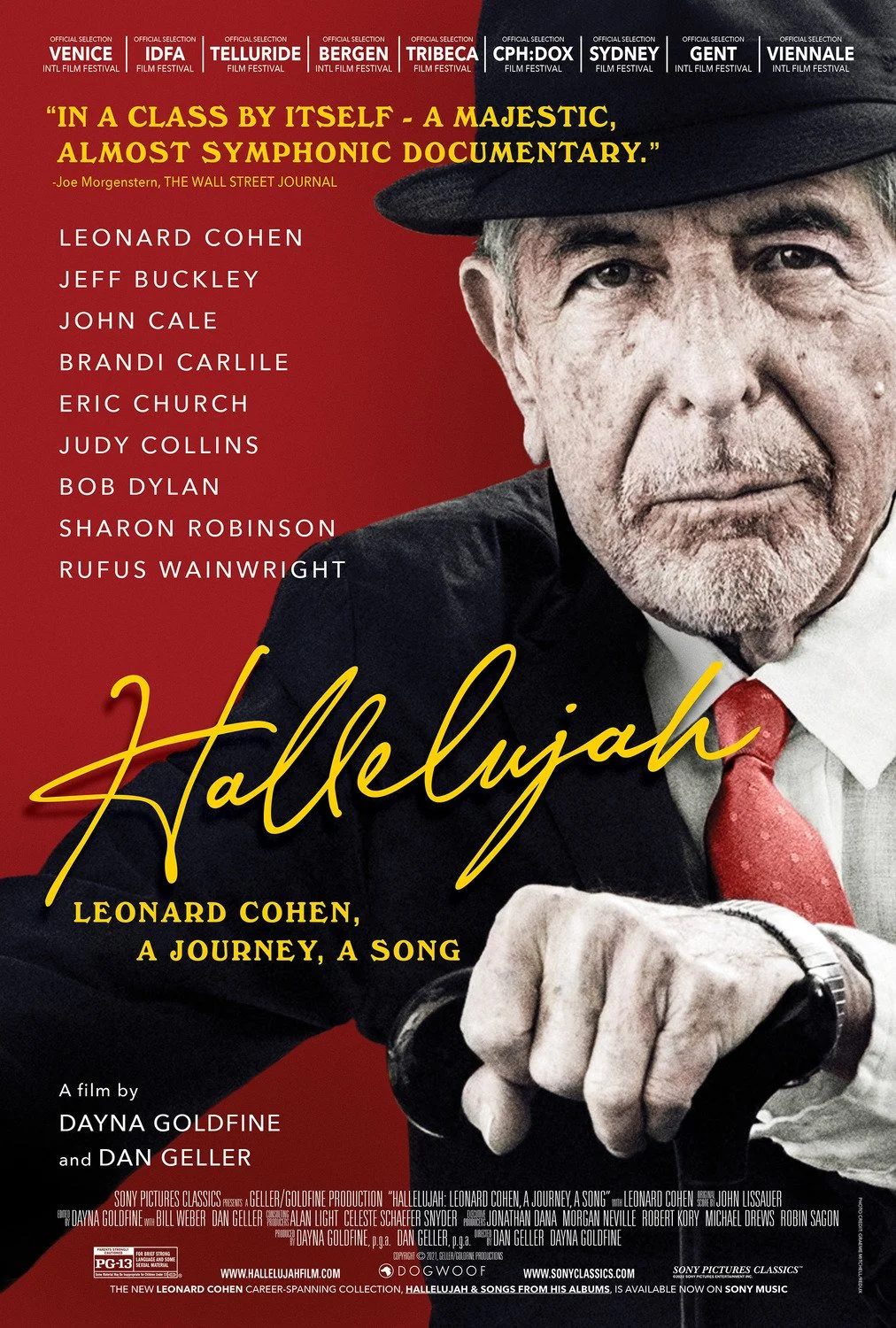

'Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song' Review: It Will Mean Exactly as Much as it Means to You

The impact which the late Leonard Cohen left upon the arts is impossible to doubt. Novelist, poet, singer-songwriter, Cohen remains a celebrated figure since his passing in 2016. His words have also been adapted and sung by countless musicians over the years. But even in Cohen’s impressive library, there is no song which left such an impression, which had such a fascinating life of its own, as the song “Hallelujah.” It is this journey which is explored and covered in the documentary Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song.

Directed by Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine, the film explores both the song and the song’s creator. As a result, we’re given a timeline where we can almost compare the successes of each to the other. Since art was first monetized, we have had to ask ourselves whether music belongs solely to the creator, the producer, the artists who cover it, the audiences who listen to it. The filmmakers even find footage where Cohen himself is questioned on the wild success of his own song. It is a question which seems to baffle him as much as anyone else. Indeed, there are moments in the timeline when the wild success of “Hallelujah” is mirrored by Cohen’s retreat to spiritual seclusion on Mt. Baldy, and the infamous betrayal by his manager which left him virtually penniless. Of course, both he and song have endured, and both have achieved an almost mythical status.

The song’s story is itself a famous one; Cohen spent seven years writing well over a hundred verses before he was satisfied. Even after his original version was released, Cohen sang it with new lyrics which gave it a whole new meaning. Was the song spiritual? Sexual? Something? And yet, after all that work, the song was unappreciated, even by the record label itself. It was saved from obscurity by other musicians discovering it and singing it for themselves. The documentary examines the early covers by Bob Dylan and John Cale, then reveals how those interpretations were discovered by a generation of new artists like Jeff Buckley (the film provides a snippet of Buckley modestly intimating that he hopes Cohen never hears his version), Brandi Carlile, Rufus Wainwright, Eric Church, and Alexandra Burke. And yes, the film Shrek is earnestly brought up as a reason for this song’s longevity (I can’t knock that fact either; Shrek is how I was first introduced to the song, and even as a kid, it haunted me).

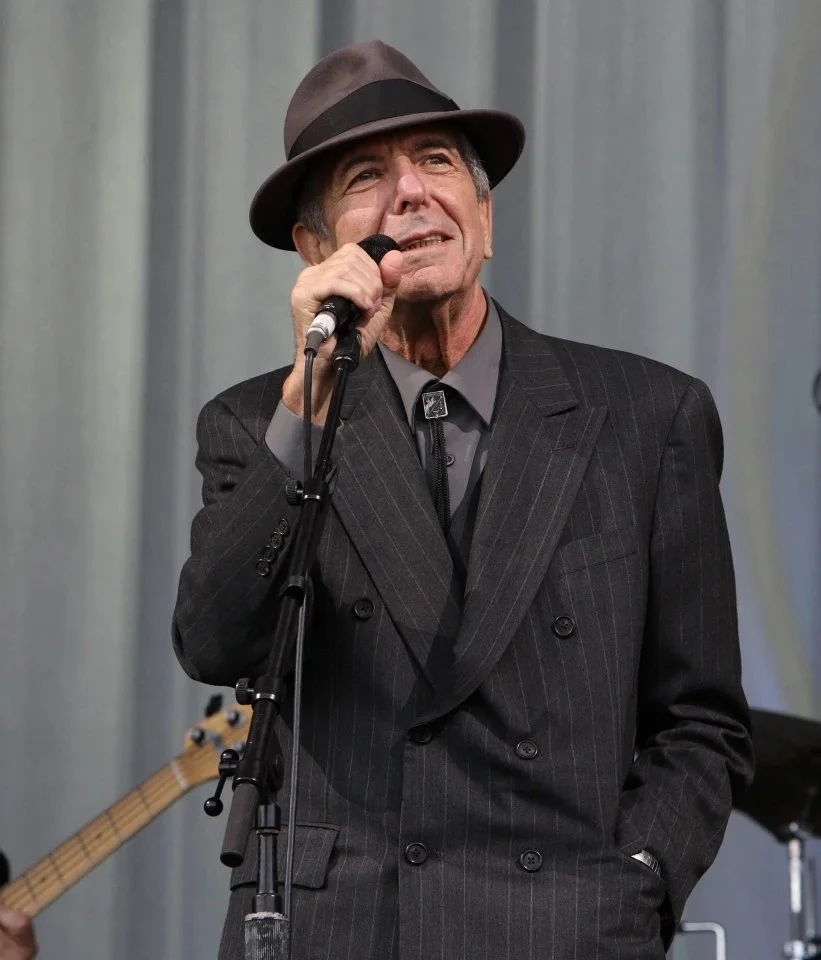

Meanwhile, we also get glimpses of Cohen’s own journey over the years. Archive footage and photographs bring Cohen back to us. Anecdotes are told which help remind us that he was a human being after all. Renowned figures such as former Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, photographer Dominique Issermann, musician Judy Collins all reflect on Cohen’s early days breaking into music, after he’d already turned 30. We hear of Cohen’s conviction that he couldn’t actually sing, and we see from subsequent interview footage that Cohen never lost this sense of vulnerable self-deprecation. There is a moment from his later years, performing into his 70s, and an audience member shouts “I love your voice.” Over the audience’s laughter, Cohen pauses to gently, almost shyly, answer her with “You’re about the only one who does.” I would have burst into tears watching that, but I was already crying before that.

Throughout the film, we are privy to interviews with a plethora of people who either had close ties to Cohen, his song, or both. There is Rolling Stone journalist Larry “Ratso” Sloman, a longtime interviewer of Cohen’s. There is Sharon Robinson, Cohen’s longtime collaborator and co-writer, and Dr. Mordecai Finley, his former rabbi. We also hear from John Lissauer, the man who arranged and produced the original 1984 rendition of “Hallelujah”, and from former Columbia Records president Clive Davis. Susan Feldman and Janine Nichols tell the story of how Buckley came to play the song. Wainwright, Church, and Carlile discuss their relationships with the “Hallelujah.” One shocking absence is renowned singer kd Lang, though the filmmakers do at least show footage of her unmatched rendition at the 2017 tribute concert to Cohen’s memory.

Fans of Cohen might want to know more about the man himself, for the documentary can only cover so much, but as I’ve indicated, this documentary moved me more than even I could ever have expected. I first listened to Cohen’s music when I was a teenager, but I was amazed not just by the music, but by the man behind that music. He seemed to exist on an entirely different spiritual level, yet he was also incredibly human. It was a true experience to see snippets of his evolution across the decades; a bashful and uncertain 30-year-old trying starting out in music, a middle-aged man meditating in monk regalia, a man returning to the stage in his 70s and showing everyone just how alive he was to the very end.

Some might accuse me of letting my personal sentiments get in the way of a film review. But this film is exactly about those strong connections which we have with art and with the artists who make them. Those strong connections are, indeed, precisely why so many renditions of “Hallelujah” exist today. This documentary is also about how a song can mean a thousand different things. How else could “Hallelujah” be played over scenes of a sulking ogre and at Jack Layton’s funeral with equal amounts of sincerity? And no, I do not doubt that this is an idealistic portrayal of Cohen himself, but for me at least, the world is a noticeably emptier place without him. This documentary was a visceral reminder of that.