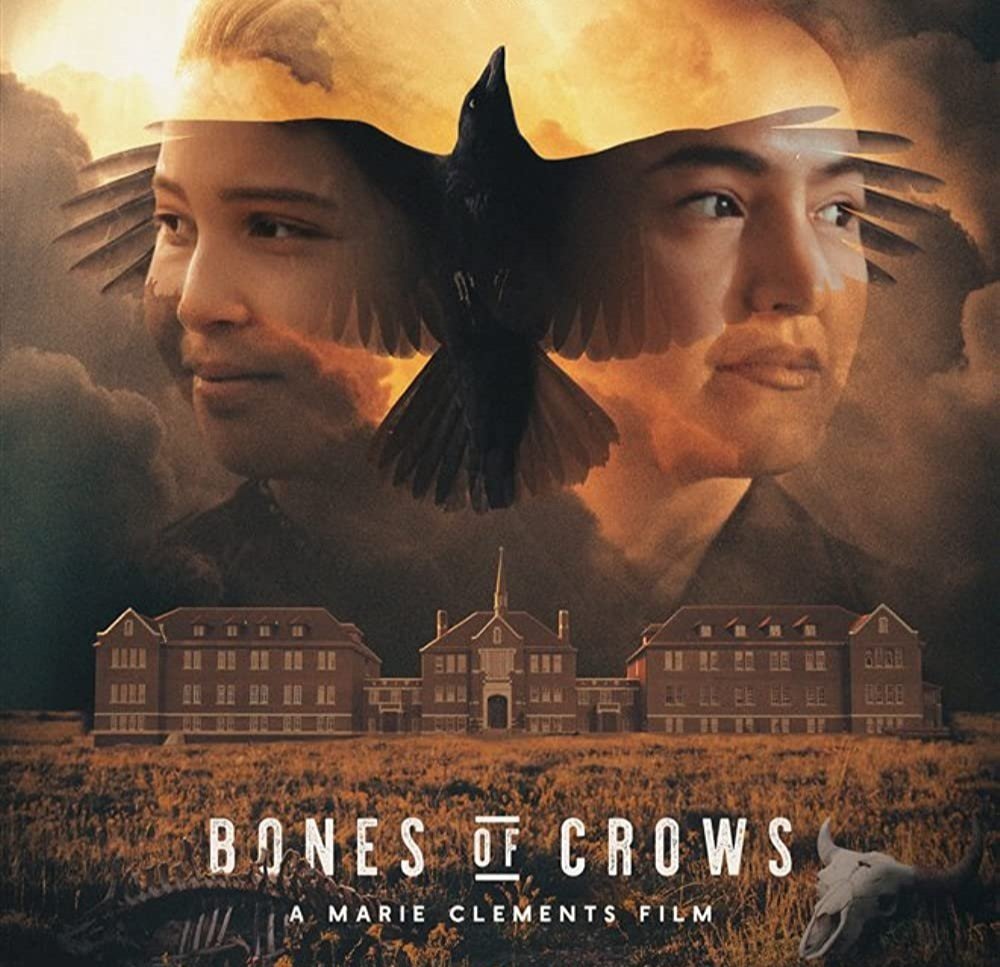

'Bones of Crows' Review: The Truth is More Horrifying Than Fiction

Beginning in the 1800s, and continuing for over a hundred years until just before the 21st century began, 150,000 Indigenous children were rounded up by the Canadian government and forcibly removed from their families. They were imprisoned in residential schools run by religious officials and overseen by the state. Thousands of those children died behind the walls of these schools, and their bodies are still being discovered in unmarked graves to this day. The survivors of those schools continue to suffer, and struggle to find some kind of peace and justice for all that they suffered. It is one thing to read about it, but quite another to see it play out in this film.

Written and directed by Métis auteur Marie Clements, Bones of Crows is a film which focuses on a Cree woman named Aline Spears (Grace Dove, Carla-Rae, and Summer Testawich). The story is an ambitious one; it stretches across nearly eighty years, with Aline being portrayed by the three aforementioned actresses at different points in time. The film presents Aline’s story in a non-linear structure, jumping through time to slowly peel back the layers of this woman’s life.

As a girl in the 1930s, she and her siblings are taken away from their parents by force. At the residential school, she is subjected to neglect and cruelty by the hands of people who see her as less than human. That changes somewhat when someone notices that she has a gift for piano playing. Father Jacobs (Rémy Girard) orders her to take lessons, hailing this as an example of the residential schools doing good for the children in their care. Thus, there is a scene where Aline plays Bach for Father Jacobs and his colleagues as they stuff their faces with good food and quote Canada’s founding Prime Minister John A. MacDonald’s policy of subjecting the Indigenous peoples with forced starvation.

Unlike several other characters in the story, Aline survives the residential school, and she enlists as a code talker during the Second World War. The film explores the little-remembered fact that several of the Allies’ codes consisted of words from the Cree language, which proved unbreakable to the Germans. In gratitude, the Canadian government not only continued to uphold the residential schools after the war, but also gave pittances to Indigenous veterans such as Aline and her husband Adam (Phillip Lewitski and Tyler Peters).

Speaking of Adam, he is one of the main supporting characters in the film. Through him, we are shown more of what the residential school survivors must go through. Adam is introduced to us as a fresh-faced young man, and he marries Aline while wearing his crisp new soldier uniform. He talks of how serving his country will allow him to prove his worth and give him a better future than he might hope. The war, however, takes its toll on him, including in a harrowing scene where he comes across Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, which trigger flashbacks to his own status as a survivor of an attempted genocide. Even before he is crippled during combat, Adam begins to self-medicate with alcohol, struggling with the injustices of his boyhood and manhood alike.

Another supporting figure in the story is Aline’s sister, Perseverance (Alyssa Wapanatâhk, Sierra Rose McRae, and Kwetca'min Dawn Pierre). Like Adam, Perseverance falls prey to addiction in the years following her time in the schools. She and Aline have a strained relationship for reasons which are revealed as the film plays out, but Aline promises nevertheless to try and find Perseverance’s children while she is imprisoned as an adult.

To go over the events of this film is to look at just a fraction of what Canada’s Indigenous population has been forced to endure for centuries. Again and again, their humanity has been denied by the Canadian government, justified through racist and colonialist attitudes which are still in effect to this day. Some might try to dismiss this film as being far too blunt, too on-the-nose, but those people have missed the point. The naked truth is on display, and it will prove devastating to sit through for many in the audience. That is also the reason why this film should be considered a mandatory viewing in high schools across Canada.

In case it was not clear yet in this review, the film is a triumph, both as a work of art, and as a record of history. The film makes excellent use of its modest budget without being limited in its scope. Its ambition is matched by the brilliant performances of everyone in the cast. The story jumps through time without ever being confusing or disjointed. Between breathtaking shots of landscapes and claustrophobic shots within the residential schools, the film’s themes are impossible to miss. Early on in the film, a sadistic nun (Karine Vanasse) ensures that the children under her watch walk in a straight line with their heads bowed in submission. Later on, Perseverance walks through a prison corridor in a similarly straight line, struggling with flashbacks to her similarly regimented and torturous childhood. Speaking of said nun, she is portrayed mostly as a bitter egotist who exploits her position and her religion to bully these children. If the film has any flaw, it is the one false note in the nun’s story, which comes near the end in an attempt to humanise her. One could make a case for having that development in the story, but it’s definitely debatable.

All in all, Bones of Crows is a challenging, harrowing portrayal of suffering, but the film does not wallow in that suffering either. Aline never stops fighting for herself and her family; she is upright even into her 80s, determined to face her oppressors and show them that they will not defeat her. There is a sense of endurance, a continuance of the indomitable spirit which will rise up to make sure that this history is never forgotten. The film might one day be considered a time capsule of how things used to be, and its very existence might one day serve as an example of how things eventually got better. One can only hope that things do change for the better, but there is so much more work to be done until then.