‘Shelby Oaks’ Review: A Disastrous Debut from Chris Stuckmann

Chris Stuckmann certainly has the cinematic baggage to craft Shelby Oaks, but he cannot effectively transcend any of the influences he cites in this painfully underdeveloped horror film.

In 2021, as he began to make the jump from discussing movies for a living to making his feature directorial debut, Shelby Oaks, film critic Chris Stuckmann made the bold decision that he would stop reviewing films he perceived as bad, citing that he “just doesn’t enjoy [trashing filmmakers] anymore.”:

“I don’t enjoy talking negatively about film. It was hard to make amateur films as a kid, and I knew that, but it’s very difficult to make them professionally as an adult, as well. Meeting filmmakers, talking to them at festivals, going onto their sets, really seeing how much work goes into even your average not-so-great movie, I just don’t feel like doing that anymore. I don’t want to talk negatively about filmmakers. I don’t want to trash filmmakers. It would be strange for me to be making movies, and also shitting on other filmmakers.”

While the decision itself is a commendable one, shifting the discussion of film to the art of filmmaking itself as he gets a taste of what goes behind making any film, whether high or low budget, one cannot control how other people will describe – or perhaps even trash – his debut into the world of filmmaking. I do not necessarily think “trashing” filmmakers effectively contributes to the critical discourse on any movie. Still, I also believe there is a place for negatively reviewing films and discussing what makes a particular work so shoddy, when audiences deserve so much better than junk that robs them of their time. There’s a reason why criticism – when done right, of course – remains an essential way for us to think about the art we consume (and not just discuss what’s good or bad about it). A good critic will, yes, discuss its merits and flaws, but also reframe what you’ve just seen to make you think about it differently.

Of course, one must approach this respectfully, without denigrating the work that went behind it (as it is very difficult to make any movie). Yet, this nixes the argument that “If you knew how hard moviemaking is, you wouldn’t trash a film,” because a good critic never crosses the line between ad hominem attacks and discussing the film’s (lack of) merit. As much as Stuckmann, who has amassed the biggest Kickstarter campaign of the site’s history to crowdfund his passion project, doesn’t want to trash filmmakers and review “bad films,” the one thing he will never be able to predict is the reception that Shelby Oakswill inevitably have in the public consciousness, and, yes, among critics. No reframing to become a “nicer” critic will be able to protect him from either adulation or vitriolic lambasting.

Did I “grow up” watching Stuckmann’s videos? Absolutely. Do I still watch them? Absolutely not – I “grew out”, so to speak, of this facile type of criticism. However, that doesn’t mean I wasn’t looking forward to a film that had its world premiere at Montreal’s best film festival, with the filmmaker and executive producer Mike Flanagan in attendance. NEON acquiring the rights to the movie a few weeks before its premiere at Fantasia also made me relatively curious to see what “getting Stuckmannized” on the big screen would feel, as it gave a sense of pedigree to the movie that Stuckmann has likely always wanted (way more than Flanagan backing it up).

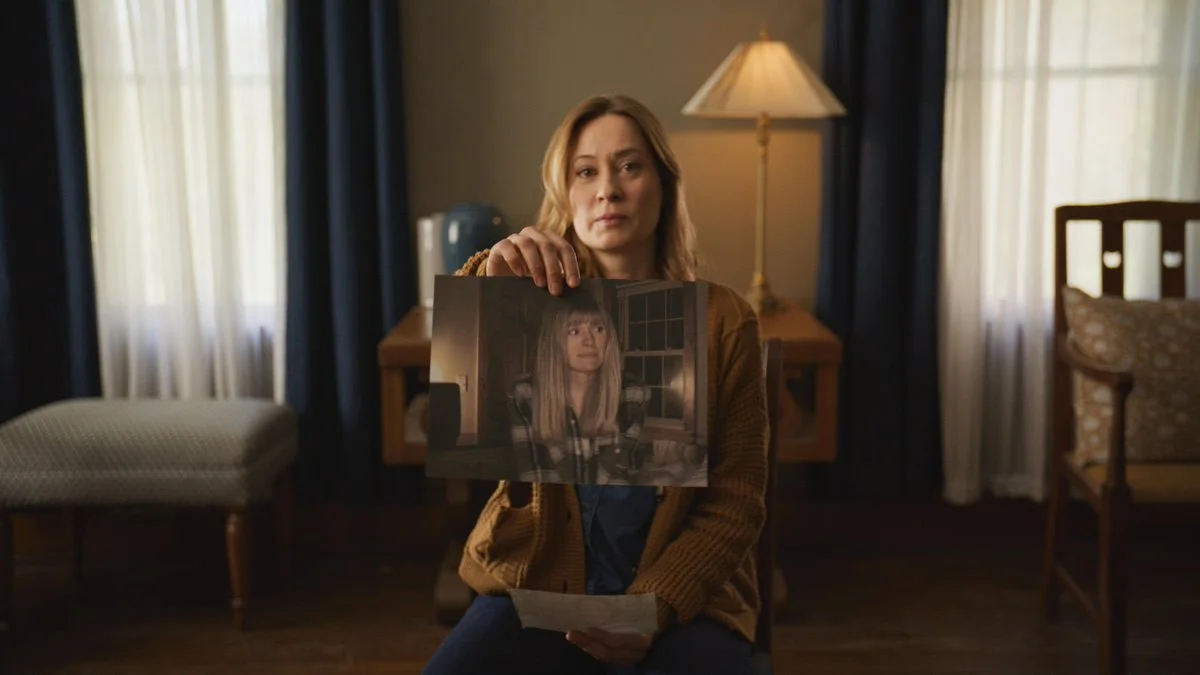

Not being able to attend the world premiere at Fantasia proved to be a blessing in disguise, since Shelby Oaks underwent three weeks of reshoots (and a fresh re-edit courtesy of Companion co-editor Brett W. Bachman) to amp up the gore and add several elements that were in Stuckmann’s original script, but couldn’t make it in the finished film due to budgetary reasons. And for the movie’s introductory half — a faux-documentary of sorts that discusses the disappearance of Riley Brennan (Sarah Durn) and the “Paranormal Paranoids,” a group of YouTubers (the metatext is absolutely here) investigating locations that may (or may not) be paranormal — I saw the vision.

Stuckmann’s analytical eye, forcing the audience to reexamine several images as Riley’s sister, Mia (Camille Sullivan) watches a tape that gives a clearer sense of why she disappeared, is second-to-none. The mélange of found footage — zoom-ins on a shrouded, shadowy figure lurking in the background, for example — and “talking head” documentary segments frames the story in an aesthetically compelling way. Found footage lends itself so well to a limited budget, which Stuckmann certainly took advantage of. When you don’t have much money, the only thing that will not impede your production is your imagination. How can one film a 20-minute intro that covers everything we need to know about the protagonists, their disappearance, and its impact on the internet and the community as a whole? The answer is clearer-than-clear.

A documentary makes exposition easier to digest, and the “found footage” aspect embedded in the opening and beyond creates a distinct atmosphere that traditional filmmaking can’t capture. So why, dear reader, must Stuckmann suddenly abandon this compelling device and transition to a dull and pedestrian supernatural horror movie we’ve all seen before, when what precedes this boldly introduces the creative side of a “content creator” we might not have known about? I couldn’t tell you the last time I saw a movie shoot itself in the foot this badly, but it happens right after Stuckmann commits the cardinal sin of turning his unique proposition into something we've seen a thousand times before in better movies.

Yes, I’ve seen The Blair Witch Project, Rosemary’s Baby, and Larry Fessenden’s Wendigo. Do you have anything else to propose beyond obvious references that are never transcended – or made unique – by their filmmaker? The documentary primer obviously riffed on Blair Witch and Lake Mungo, but Stuckmann’s voice was found. There’s a cheeky nod here and there, but it’s not too evident for those who have never seen these films or are unfamiliar with the found footage subgenre as a whole.

As soon as Stuckmann shifts his aesthetic approach, Shelby Oaks becomes a grab bag of ideas from other horror movies, set inside a story that suddenly refuses to interrogate the images it presents to the audience (unlike the “documentary” portion) and develops nothing as the mystery behind Riley’s disappearance begins to clear up. The first twenty minutes are full of metatextual elements about Stuckmann’s YouTube days and his past as a former Jehovah’s Witness, and one almost wants the entire movie to be like this, because it feels personal and true to who he is as a human being. The rest of Shelby Oaks lacks the personality of this liberating opening and instead bludgeons the audience with rapidly edited sequences that are essentially loud jump scares and intense, punishing gore, none of which is remotely compelling.

We’re also never given a concrete reason to care about anyone on screen, with most of the supporting characters (played by Brendan Sexton III, Michael Beach, and Keith David, with the latter obviously stealing the show) appearing for one scene or two. The bulk of the movie is Mia’s story, and the choices she makes to find her sister are often so ridiculously convenient that they remove any sense of dread and tension Stuckmann establishes. Camille Sullivan’s performance is unimpeachable, and the pain she feels as Mia looks for anything that might point her to her sister’s whereabouts is enough to make anyone feel for her, despite the flimsy material she has to work with that consistently betrays her at every turn.

Worse yet, the “traditional film” portion of Shelby Oaks reeks of a student production with zero formal intuitiveness on display. Of course, the budget is low, meaning resources are limited —which is completely fine —but every image is stolen from someone else, without Stuckmann wearing the influences he adopts on his sleeves and making the world he haphazardly develops his own. The biggest sin of the movie is its inability to commit to a singular vision and aesthetic. With all of these significant influences guiding him to write the screenplay, it feels so odd that he can’t develop anything past what he introduces. However, those aspects are challenging to mention without spoilers.

Let’s just say that if you’ve seen the aforementioned movies in this review, you’ve seen Shelby Oaks, even when it ends on a telegraphed – and downright revolting – conclusion that exploits the characters’ pain in completely illogical ways, even for a supernatural film’s standards, since we’re never given a reason to care about anyone on screen. The ending also raises far more questions than answers, baiting the audience into a sequel rather than offering any satisfaction that this endeavor into crowdfunded cinema (which, let’s be honest, rarely results in anything good) was worthwhile.

The never-ending end credits sequence (which likely takes up about fifteen minutes of its brief 91-minute runtime) does prove that it takes a village for a movie like this to get made, and one has to commend Stuckmann for pursuing his dreams. I’d just hoped it’d be more substantial than whatever the hell this is. Stuckmann can say he will stop negatively reviewing films. Yet, the desire of a critic to ask their filmmakers to be better than the facile screenplays they write will continue to live on, even if shrouding yourself in positivity will momentarily stop the dissenting voices from populating your mind, until it inevitably becomes the consensus. Filmmaking is hard, yes, but criticism is vital for the art form to survive and overcome the mediocre streak it is currently undergoing.

That said, Stuckmann’s dedication to moviemaking is appreciated, and one hopes he continues in that direction. It’d be a real shame if the hostile reception to Shelby Oaks would stop his resolve to make movies altogether and return to a brand of criticism he has never truly evolved on YouTube. After all, as Park Chan-wook so eloquently said, “there’d be nothing worse than a film critic trying to make a film and it turns out to be a bad film, and then they have to come back and work as a critic again – you would’ve lost your trust with your readers, because if you’re a bad filmmaker, they don’t want to trust your reviews.”