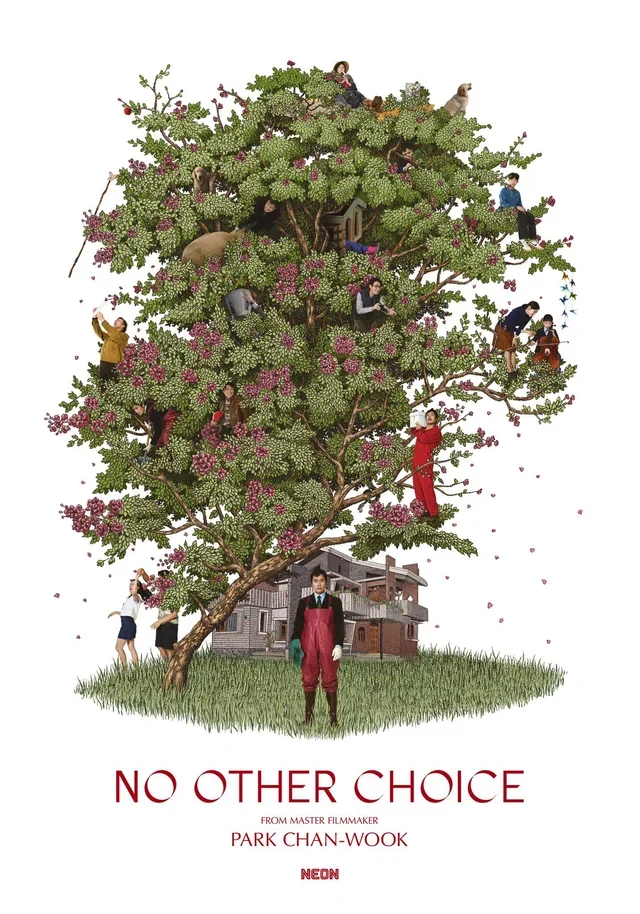

‘No Other Choice’ Review: Park Chan-wook’s Masterpiece of Pure Cinema [TIFF 25]

Park Chan-wook redefines his filmography with his adaptation of Donald Westlake’s ‘The Ax’ in ‘No Other Choice’ and offers a once-in-a-generation lesson of Pure Cinema that anyone who APPRECIATES the art form must see.

“Pure cinema” is a simple, but effective, term, to describe telling a story in purely visual terms, without the use of dialogue. Strong images are all we need to tell something compelling – either through the juxtaposition of images, or the lone image itself. Alfred Hitchcock was a purveyor of such a practice, and emphasized images (and montage) first before telling his story with the use of dialogues. Sometimes, Bernard Hermann’s music would create a sense of rhythm, especially in how a scene would be cut, but the image is above all the most essential tool in pulling the audience into the film and imbuing each frame with as much tangible meaning as possible for anyone to extract something out of them.

It seems only natural that the biggest scholar of Hitchcock’s work, Park Chan-wook, returns to moviemaking with his most exemplary lesson in pure cinema yet: No Other Choice. This lesson, which any avid moviegoer must see, unfolds in two parts. First, Park sets up the descent into madness that our protagonist, You Man-soo (Lee Byung-hun) goes through after being fired from his job. The capitalist society he has fed has disposed of him as if he was nothing, which puts great stress on the already precarious situation his family lives in. They have canceled their kids’ various extracurricular activities, have started the process of perhaps selling their house and – gasp – even pulled the plug on Netflix!

Promising to his wife (Son Ye-jin) that his career will get back on track, Man-soo is beaten by the multiple hurdles capitalism has set out for him and is immediately spit back out without being given a fighting chance. And, after being rejected by a paper company he wants to work for, his last chance at wanting to be in the same field of work that has given his life so much, Man-soo believes he has “no other choice” (ha) but to eliminate potential competitors who are also vying for the same job. What unfolds is a darkly funny and visually soul-shattering exploration of the limits one will test to attain their “dream job” after their “purpose” to serve a machine that never rewards them meaningfully in any way is taken from them.

The second part of the lesson occurs after all has been established, and all Park must do at this point is to visually represent the torment Man-soo lives in so we, in turn, start to feel for the man even when he starts to…*ahem*...kill people. But things don’t go as they plan (they never do in cinema), and this is where the filmmaker bathes in genre excess where his hallmark stylistic flourishes are on full display. A bravura sequence at the top of the movie’s first hour, where the repetitive use of Cho Yong Pil’s “Red Dragonfly” deafens the speakers to the point that dialogue exchanges between Mon-soo and his rival candidate, Gu Bummo (Lee Sung-min), are barely perceptible, is the ultimate demonstration of why Park is a league ahead of his contemporaries. We’re forced not to listen in (the subtitles do help, but the dialogues aren’t important), but to feel the palpable tension rising as the music gives the right tempo to how Chan-wook dictates how the scene is edited, and, more importantly, how the camera moves.

Each image, deftly shot by Kim Woo-hyung, acts as a shock to the system. Some of his most storied hallmarks – superimpositions, unhinged camera angles, second screens peering into the first – are present in this 139-minute dark comedy. However, the most intriguing angles are new, never-before-realized movements that punctuate the drama and add immense texture to a career-best turn from Lee Byung-hun. His performance as Mon-soo is often amusing, but is undercut by tangible dramatic power as someone who wants to desperately get back in a machine that has never given him anything concrete, and won’t give him a form of reward if, by some miracle, he pulls off his plan successfully.

Two detectives think he may have something to do with the murder, but aren’t entirely sure. In any case, Mon-soo’s resolve has never been this strong, but is it worth it? This is at the heart of Chan–wook, Don McKellar, Lee Kyoung-mi, and Lee Ja-hye’s screenplay, who adapt and change Donald Westlake’s The Ax to fit our modern, automated times, in ways that the author of the source material did not envision. We understand Mon-soo’s passion and sincere devotion to the art of paper-making, which, we eventually learn, has been replaced by cost-efficient machines that have taken over the man-made labor that gave the protagonist the purpose he had always dreamed of. Capitalism doesn’t reward the humans who make it function, but only the ones at the top who don’t care about the ones whose livelihoods are impacted by their decisions.

It’s a fairly damning indictment that could draw comparisons to Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, but what sets the movie apart from the Academy Award-winning picture is how Chan-wook ends his film, not with a quasi-hopeful note, but with a stark and urgent warning. Mon-soo’s quest to eliminate the competition is already futile from the start. However, it becomes even more fruitless as the movie progresses, culminating in its devastating final scene, all told through the use of visuals before a character utters any dialogue.

Man-soo has been conditioned to believe that his life will amount to something if he works in a system that only robs him of his time and gives him nothing back. None of it is more apparent during its tragic ending, which seems like a victory for the protagonist, but is in fact the ultimate death sentence, not only for him, but for the entire planet. There’s an art to paper making that Man-soo wants to preserve, but what does that art kill? When you’ve answered this question, you may not want to root for him after all.